I Was Bitten by a Bat

- Marlane Ainsworth

- May 19, 2023

- 5 min read

And read, The Lost Art of Dying, by L. S. Dugdale, MD.

Bitten by a Bat

A bat was flying around inside our house when we returned after an absence of five days. Its black wings of tightly stretched skin looked like half-erected pop-up tents as it flitted quickly and silently around the kitchen.

I know all about bats. They’ve existed for more than 50 million years. They love the moonlight. And when they’re not eating mosquitoes or fruit, they suck warm human blood.

I respected its right to be on the earth, but I didn’t want one in my house sniffing out my warm human blood. So, Rob and I opened the kitchen and lounge room doors wide, hoping it would be lured outside by the occasional glimpses of moonlight emerging from behind rainclouds. It headed upstairs instead and circled the bedroom, so Rob opened the sliding glass door leading onto a small balcony.

‘Shoo, shoo,’ I said, hoping the species had picked up some English over the years.

By the time we’d finished unpacking the car, had a shower, and consumed dinner, we decided the bat must have left because of the simple reason that we hadn’t seen it for a couple of hours. Relieved, we shut the doors and went to bed.

I always read a couple of paragraphs of witty novels by P. G. Woodhouse before shutting my eyes, so, as usual, I reached across for my reading glasses on the bedside table. That’s when I was bitten by a bat!

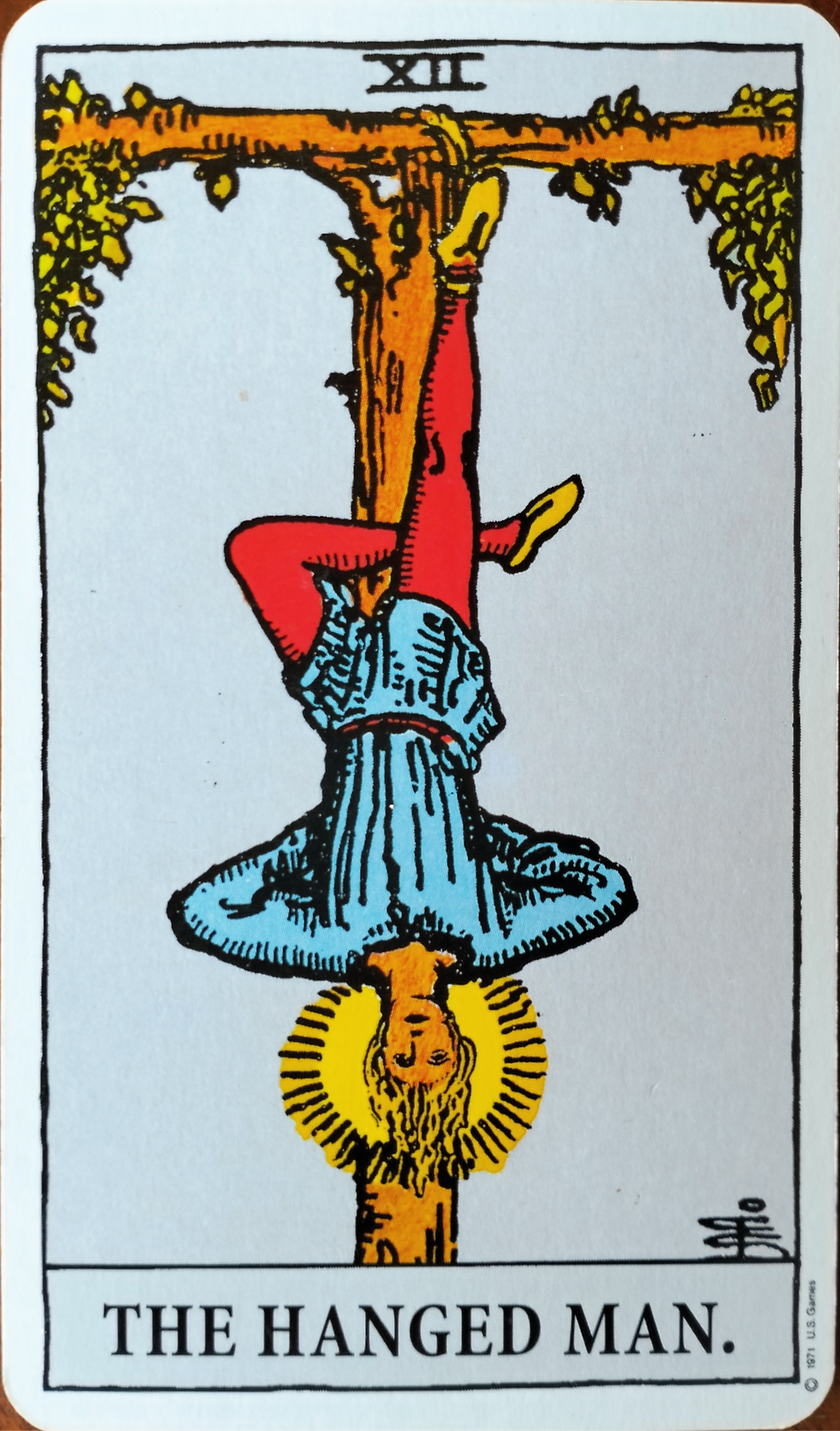

The bat hadn’t left the premises. It had been hanging upside down from the edge of my small bedside table, cleverly camouflaged against the dark wood.

I let out a little scream, flicked my arm to release its grip, sat up, and looked over the edge of the bed. The bat lay spread-eagled on the floor, obviously stunned. My hero, Rob, got out of bed, scooped it up using a jug and tea towel, grabbed a torch, and took it outside. I bathed the stinging wound on the underside of my right arm, just above the elbow, and counted five little teeth marks forming a circle.

Back in bed, I did what most people do in emergencies these days: I Googled to find out how long I had to live. The answer was – not long if the bat carried the rabies virus. The only way to know that was to take the bat along to the Public Health unit for testing.

When Rob returned, chilled and slightly damp from the wind and rain, and began to slip gratefully between the warm sheets, I said, ‘We need the bat.’

We live on a 20-acre property. Rob had taken the bat way past where the water tanks were near one of our fence lines, to ensure it wouldn’t return. But out he went again, for my sake. However, he returned without the bat. It had revived and flown away.

Further Googling revealed that rabies isn’t carried by bats in Australia, but the bats here can carry the bat lyssavirus, which is similar. The symptoms involve paralysis, delirium, convulsions, and death, usually within a week. Next, I read that the three cases of lyssavirus infection recorded in Australia resulted in three deaths in the state of Queensland, which is why I ended up at the Emergency Department of the hospital in Albany.

As a result, I had to have immunoglobulin infiltrated into each tooth bite wound and a series of four vaccines spread over the next fortnight.

I’m not brave with needles, so it took two doctors to administer the immunoglobulin – one doctor to jab me in the five tooth bites, and the other to rub and pat my feet while uttering encouraging comments like, ‘You’re doing well,’ and ‘It will soon be over.’ Then a nurse gave me the first of the four rabies shots, and, seeing as the three of them had me trapped on the hospital bed, the nurse also took the opportunity to administer a diphtheria-tetanus shot, which I’d let lapse.

My ordeal was over. The doctor who’d rubbed my feet now tenderly placed a warm blanket over my legs and told me to rest for twenty minutes. If I was feeling alright after that time, I could leave.

Thankfully I’d bought a book with me, so I lay there in the Emergency Department and read my latest literary purchase, which happened to be, The Lost Art of Dying, by L. S. Dugdale, MD. Most appropriate, I thought, as I lay there, shocked, battered, and nursing two arms I was sure were now badly bruised.

On pages 207-208, I read:

. . . none of us escapes our appointment with death. The solution is neither to flee it nor to seek it out. Rather, we must each prepare for [it]. Death is part of life. The art of dying well must necessarily be wrapped up in the art of living well.

I’ve written this experience in a lighthearted style, but reading this book about death while I lay in Emergency had more meaning to me than reading it at home in my favourite chair by the glass sliding door, a cushion at my back, and a coffee on the side table. Her words carried more power while I lay there, suffering a little.

Like everyone, I have an appointment with death. It probably won’t be a direct result of the bat bite if those four vaccine shots do their job, but my death will come. And Dugdale, from her experience as a medical doctor, and the founding codirector of the Program for Medicine, Spirituality, and Religion at Yale School of Medicine, writes that the art of dying well lies in living well.

We think of living and dying as opposites. But they’re inextricably bound up in each other. Life and death are co-joined, intimate, twins, dwelling within the womb of our existence since conception.

We can’t have one without the other.

Doctors, nurses, vaccines, medical procedures, drugs, transplants, herbs, or elixirs can extend our life, but nothing can stop our ultimate death.

So, as we live, we should also consider our death from time to time, as advised by the world-renowned psychotherapist Irvin Yalom, in his book, Staring at the Sun: Overcoming the Dread of Death. Not in a morbid way, but in an honest and bold way, every now and then. Like I was forced to when bitten by a bat.

Doing this will change the way we live.

NB: I’ve since found out that only about 1% of bats consume mammalian blood, and not all bats are attracted to moonlight. But they have been around for 50 million years and deserve respect.

And belated thanks to Dr Maria Soldini, for patting my feet.

With love, Marlane

I am glad you made it. It is hard to find a writer with a good Western Australian sense of humor. I mean who uses a torch to pick up a bat? I know by my on South Alabama experience you mean a bundle of sticks wrapped in rope dipped in gasoline and lit with a fire match to scare the bat. Hard to find good talent these days.